Revolt of 1 Prairial Year III

| The insurrection of 1 Prairial Year III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolution | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

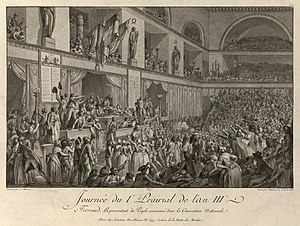

The insurrection of 1 Prairial Year III was a popular revolt in Paris on 20 May 1795 against the policies of the Thermidorian Convention. It was one of the last popular revolts of the French Revolution.[1] After their defeat in Prairial, the sans-culottes ceased to play any effective part until the next round of revolutions in the early nineteenth century. To a lesser extent, these movements are also important in that they mark the final attempt of the remnants of the Mountain and the Jacobins to recapture their political ascendancy in the Convention and the Paris Sections; this time, though they gave some political direction to the popular movement which arose in the first place in protest against worsening economic conditions, their intervention was timorous and halfhearted and doomed the movement to failure.[2]

Causes

[edit]The abandonment of the controlled economy provoked a frightful economic catastrophe. Prices soared and the rate of exchange fell. The Republic was condemned to massive inflation and its currency was ruined. In Thermidor, Year III, assignats were worth less than 3 percent of their face value. Neither peasants nor merchants would accept anything but coin. The debacle was so swift that economic life seemed to come to standstill.[3]

The insurmountable obstacles raised by the premature reestablishment of economic freedom reduced the government to a state of extreme weakness. Lacking resources, it became almost incapable of administration, and the crisis generated troubles that nearly brought its collapse. The sans-culottes, who had unprotestingly permitted the Jacobins to be proscribed, began to regret the regime of the Year II, now that they themselves were without work and without bread.[4]

The insurrection

[edit]A pamphlet published on the evening of 30 Floreal (19 May 1795), entitled Insurrection of the People to obtain bread and reconquer their right, gave the signal for the movement. This pamphlet, which was known as The Plan of Insurrection, provided the popular agitators with definite objectives, the first of which was expressed in a single word: Bread! Its political aims were expounded at greater length: putting the Constitution of 1793 into practice, election of a legislative assembly to take the place of the Convention, the release of imprisoned patriots. The people were asked to march in a body to the Convention on 1 Prairial. There can be no doubt about the preparation of the insurrection by the sans-culottes leaders. As early as 29 Germinal (18 April), Rovère had reported a plot to the Convention. As for the deputies of the Left, their attitude on the first of Prairial showed that they looked favorably on the movement, yet did nothing to organize or direct it.[5]

First round

[edit]

Félix Auvray, 1831

Early on 1 Prairial the tocsin was sounded in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and the Jardin des Plantes. Once more, as in October 1789, it was the women that took the initiative and brought their menfolk into action with them. In the Faubourg du Nord (Saint-Denis) they called the men out from the workshops at 7 o'clock in the morning. There were food riots and assemblies of women at bakers' shops in Popincourt, Gravilliers, and Droits de l'Homme. As they marched, they compelled women in shops and private houses, and riding in carriages, to join them. They reached the Place du Carrousel, in front of the Tuileries, at 2 o'clock; pinned to their hats, bonnets, and blouses were the twin slogans of the rebellion, Du Pain et la Constitution de 1793. Thus equipped, they burst into the assembly-hall, but were quickly ejected. They returned with armed groups of the National Guard an hour later.[1]

Meanwhile, a general call to arms had been sounded in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine; men quickly armed and followed the women to the Tuileries. A similar movement began in the Faubourg Saint-Marcel and in the central neighborhoods. In some cases, a minority of insurgents forced the doors of the armories, distributed arms to their comrades, and compelled their commanders to lead them to the Convention.

The second invasion of the Tuileries quickly followed. Deputy Jean-Bertrand Féraud, who opposed their entry, was struck down and his head was severed and paraded on a pike. This time the women were amply supported by armed citizens of the rebellious sections, though few battalions broke into the building in full strength. Yet the demonstrators were in sufficient numbers and their weapons sufficiently imposing to reduce the majority to silence and to encourage the small remnants of deputies of the Mountain, The Crest ( la Crête de la Montagne ), to voice their principal demands – the release of the Jacobin prisoners, steps to implement the Constitution of 1793, and new controls to ensure more adequate supplies of food. These were quickly voted and a special committee was set up to give them effect. But the insurgents, like those of Germinal, lacked leadership and any clear program or plan of action. Having achieved their immediate objective, they spent hours in noisy chatter and speech-making. This gave the Themidorian leaders time to call in the support of the loyal sections – with Butte des Moulins (Palais-Royal), Museum (Louvre), and Lepeletier at their head – and insurgents were driven out the Tuileries.[6]

Second day

[edit]The armed rebellion continued the next day. From 2 o'clock in the morning, the call to arms had sounded in the Quinze Vingts. The tocsin tolled before 10 o'clock in Fidelite (Hotel de Ville) and Droits de l'Homme. In these two sections and in Arcis, Gravilliers, and Popincourt illegal assemblies were held. The three sections of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine sprang to arms and marched on the Convention, led by Guillaume Delorme, a wheelwright and captain of the gunners of Popincourt. Supported by some sections of the center, they appeared on the Place du Carrousel at 3:30 in the afternoon, loaded guns and trained them on the Convention. General Dubois, who commanded the Convention forces, had 40,000 men under him; the insurgents may have numbered 20,000. It was the largest display of military force drawn up for battle that had been seen in Paris since the Revolution began. But no shots were fired: when the Convention's gunners and gendarmerie deserted to the opposing side, the insurgents failed to follow up the advantage. Towards evening negotiations began; petitioners were received at the bar of the Assembly, repeated their demands for bread and the Constitution of 1793 and received the presidential embrace. Lulled by vain hopes of promises to be fulfilled, the insurgents thereupon retired to their various sections.[7]

The defeat

[edit]But the Convention was determined to make an end of the business. On the morning of 3 Prairial regular army units were mustered, in addition to the jeunesse dorée and battalions of the western Sections, and preparations were made to enclose the Faubourg Saint-Antoine within a ring of hostile forces. The jeunesse made a premature sortie into the faubourg and was forced to retreat, and Saint-Antoine workers rescued from the police one of the assassins of Féraud on his way to execution. But, during the night, the Government overcame the resistance of most of the other insurgent Sections; and, on the 4 Prairial, the faubourg was called upon to hand over Féraud's murderers and all arms at its disposal: in the event of refusal it would be declared to be in a state of rebellion and all Sections would be called upon to help to reduce it by force of arms or to starve it into surrender. Meanwhile, an army under General Menou prepared to advance against the rebels.

Their situation was hopeless; yet some attempt was made in other Sections to bring them relief. In Poissonnière Étienne Chefson, a cobbler and old soldier of the armée révolutionnaire, was later arrested for trying to organize building workers of the rues d'Hauteville and de l'Échiquier to march to the help of the faubourg; in Arcis and in Finistère, there were shouts, even after the battle was lost. But no material support was forthcoming; and the faubourg surrendered, a few hours later, without a shot being fired. The movement was totally crushed.[7]

Reaction

[edit]

Les derniers Montagnards

Charles Ronot, 1882 (Musée de la Révolution française)

This time, the repression was thorough and ruthless. It struck both at the leaders – or presumed leaders – of the insurrection itself and at the potential leaders of similar revolts in the future: to behead the sans-culottes once and for all as a political force it was thought necessary to strike at the remnants of Jacobins in the Convention and in the Sectional assemblies and National Guard. Twelve deputies were arrested, including six that had supported the demonstrators' demands on 1 Prairial. On 23 May (4 Prairial), a Military Commission was set up for the summary trial and execution of all persons captured with arms in their possession or wearing the insignia of rebellion. The Commission sat for ten weeks and tried 132 persons; nineteen of these, including six deputies of the Mountain, were condemned to death.

The murderers of Feraud, the gendarmes who had gone to over to rioters, and the deputies Romme, Duquesnoy, Goujon, Duroy, fr:Pierre-Amable de Soubrany and Bourbotte were all lumped together in the same category. The condemned deputies, wishing both to demonstrate their inviolable liberty and to challenge their accusers, attempted to kill themselves before being conducted to the scaffold. The first three were successful. Soubrany died as he reached the guillotine; the others were executed alive. This 'heroic sacrifice' put the 'martyrs of Prairial' in the pantheon of the popular movement. But it highlighted the insoluble contradiction of their position. On 1 Prairial the most lucid of them understood the trap which was set up for them and consciously walked into it.[8]

The Sections were invited to hold special meetings on 24 May to denounce and disarm all suspected 'terrorists' and Jacobin sympathizers. The result was a massive toll of proscriptions, in which the settling of old scores played as large a part as the testing of political orthodoxy. By the 28 May the Gazette française already put their number at 10,000; and the eventual total of arrested and disarmed must have been considerably larger, as, in several Sections, all former members of Revolutionary Committees, all soldiers of the armée révolutionnaire were arrested or disarmed irrespective of any part they may have played in the events of Germinal or Prairial. The precedent thus established was to be followed on more than one occasion during the Directory and Consulate.[9]

Why were the Parisian sans-culottes defeated in May 1795? Partly it was for lack of a clear political program and plan of action; partly through the weakness of the deputies of the Mountain; partly through political inexperience and the failure to follow up an advantage once gained; partly, too, through the correspondingly greater skill and experience of the Convention and its Committees and the support that these were able to muster – even without the active intervention of the regular army – from the jeunesse dorée and the merchants, civil servants, and monied classes of the western Sections. But, above all, the sans-culottes failed to secure and maintain in Prairial, as they had in the great journées of 1789–1793, the solid alliance of at least the radical wing of the bourgeoisie. When this faltered and failed, their movement for all its breadth and militancy, was reduced to a futile explosion without hope of political gains.[10]

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Lefebvre, Georges (1963). The French Revolution: from 1793 to 1799. Vol. II. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-02519-X.

- Rude, Georges (1967). The Crowd in the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-00370-5.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1964). The Thermidorians & the Directory. New York: Random House.

- Woronoff, Denis (1984). The Thermidorean regime and the Directory, 1794–1799. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28917-3.

- Soboul, Albert (1974). The French Revolution:: 1787–1799. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-47392-2.

- Hampson, Norman (1988). A Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-710-06525-6.